While researching for an unrelated post I stumbled upon an article which had me mesmerized enough to journey on a major diversion of such proportion that I still can't remember what it was that I was originally looking for.

While researching for an unrelated post I stumbled upon an article which had me mesmerized enough to journey on a major diversion of such proportion that I still can't remember what it was that I was originally looking for.The great gimmick these days seems to be trying to set yourself apart and garner attention by calling whatever you are doing an "extreme" something. "Extreme Makeover," "Extreme Sports," … "Extreme Politics," "Extreme Tree Hugging." You get the idea.

So I was a little taken back to see the title: "Extreme Sleepovers" – sorta sounds like something your teenage son is begging for you to authorize over spring break. It turns out however, that if anything has the real right to call itself "Extreme" anything it's this: doing research on Mt. Everest.

The term was coined to describe a series of articles by researchers at Cambridge University. Research isn't always done in a lab – often it takes a scientist and his subjects to the field… offroad so to speak. The web-master is giving twelve researchers an opportunity to write about the most unusual and difficult places they've spent the night while gathering data for their studies.

It just so happens that the first of the twelve turned out to be a master story-teller and went to Mt. Everest. You may have seen the TV program recently about physiologist Dr Andrew Murray who helped study responses to extreme altitude as part of a program that will improve hospital treatments for critically ill-people.

Even though I've tried several times to paraphrase/recapitulate his story, it just doesn't convey the intensity like his own words do. Let me quote a part of it and be sure to go read the full article. In addition, there are the reports of the eleven other researchers who went "off-road" with an "extreme sleepover."

“I won’t sleep well tonight, not with the nightmarish sounds coming from the sleeping bag next to me. Nick, my PhD student-cum-tentmate, has been struggling to control his breathing for the past hour and I recognize the classic signs of Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

I wonder whether to be more perturbed by this human terror or the night’s external soundtrack – the rumble of an avalanche on the South Col and the shotgun-like cracks in the ice of the Khumbu Glacier on which our tent is pitched.

My most pressing concern is closer to home. My kidneys have been working overtime to fine-tune my blood pH, helping me to acclimatize and my bladder is fit to burst. It’s -20°C outside and a toasty -7°C in the tent, so I’m not moving until morning. No, I won’t sleep well tonight, but I never do on my first night at altitude.

In the morning the world feels different. I’m breathless from simply pulling on my boots, but as I step into daylight, I gaze at the mountain giants around us: Pumori, Lhotse, Nupste, and the mother goddess of the world herself, Sagarmatha – Mount Everest.

Strange pillars of ice rise in desolate contrast to the waterfalls and rhododendron forests we trekked past on our way here. No rock flowers and no birds here; just a few dozen yaks and 5000 tents to remind us that this is not some lifeless alien planet, but an extraordinary environment on the roof of Planet Earth.

Everest Base Camp is a cosmopolitan canvas city constructed upon rock and ice – an epicenter of the world’s mountaineering ambition.

Next to our camp, a Malaysian expedition is raising their national flag, and on a hillock nearer the ice fall, the Scouts have set up their camp. Their manager scuttles between tents, wielding a satellite phone, while an expedition Sirdar fries eggs for breakfast, using only the magnified light of the morning sun as fuel.

As prayer flags flap in the breeze, sounds of a puja ceremony greet us. Chanting gives way to the clanging and banging of pots and pans. The climb has been blessed, and a team is readying for departure.

The wise Sherpa checks his ropes, while the Everest first-timer fiddles with her pack, gazing upwards towards her destination.

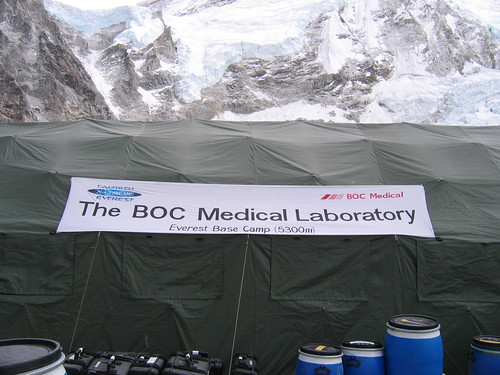

There’s little time for idle wonder. We’re here as members of Caudwell Xtreme Everest, a large-scale medical research expedition, attempting to understand how our bodies respond to low oxygen at extreme altitude in order to help critically ill patients at home, for whom low oxygen can be life-threatening.

Before breakfast, we complete our diaries – some are simple measures of mood, appetite and headache, but there’s also a step test, throughout which we monitor heart rate, blood pressure, hemoglobin saturation's and breathing rate.

The test that was light exercise back in London and Kathmandu feels Herculean up here where there is half the oxygen to which our lowlander bodies are accustomed. I pity our teammates struggling with the same test 1000 metres above us in the Western Cwm.

The tests get tougher, though I’d rather pedal to exhaustion on an exercise bike than give another blood sample; I never did get along with needles. Most embarrassing for a Cambridge academic are the cognition tests. What was a doddle at sea level becomes impossible at this altitude. I struggle to recall a list of 15 words or join together some numbered dots.

As the light fades and temperatures plummet, we make our way to the mess tent. Exchanging stories of red blood cell counts and resting heart rates, we while away the evening until it’s time for bed.

Stepping outside, I see a clear night sky awash with constellations and spend a moment counting satellites and shooting stars. A light blinks from the ridge above the icefall. A head-torch: perhaps one of our own team preparing for the next stage of their summit attempt.

I’ll sleep really well tonight, I always do on my second night at altitude.

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Thanks for taking the time to leave a comment. I will, of course, be moderating all comments to make sure (a) they conform to the standards of good taste set forth by Offroading Home; and (b) nope that's pretty much it.